Kenneth Toovak died last week at the age of 86. I had not known that he had fallen ill and was greatly saddened to learn of his death. I am told that he was in the Alaska Native Medical Center in Anchorage, but that he was going to be released and allowed to return to Barrow. He was excited about that, I am told, and was looking forward to being home for the Thanksgiving feast, which, in Barrow, means something a bit different than it does elsewhere.

I remember the first Barrow Thanksgiving feast that I attended. I journeyed through the dark day and the deeply sub-zero air to the Utqiagvik Presbyterian Church, which was packed with people. Kenneth spotted me right after I entered the door and invited me to come and sit with him. I did - although I jumped up and down quite a bit to take pictures.

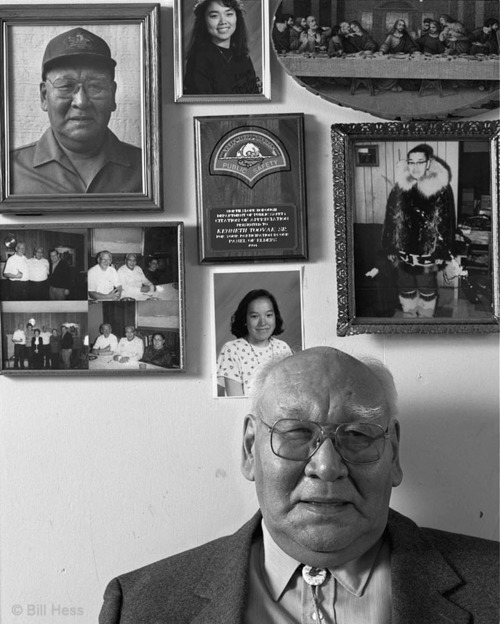

The feast began when servers holding a variety of dishes from duck and caribou soup to frozen fish, Eskimo donuts and the various parts of the bowhead whale, stood in front of the late Reverend Samuel Simmonds (seen on the wall behind Kenneth - just below Jesus at The Last Supper), who asked the Lord to bless it all.

The soups were served first and then the feast progressed through the other dishes into the whale. At first, I tried to eat everything that was given to me, but the servings just kept coming and coming and, after I had gorged on a few days worth of food, Kenneth gave me some large, freezer bags to put my extra maktak and quak in to take home and eat later.

Kenneth invited me to come over to his house later to dine on turkey. I was too stuffed to eat one more bite. I went back to the place where I stayed, flopped down on the bed and fell fast asleep until late that night - because that is what Eskimo food consumed in large quantities and dipped in seal oil will do to you.

Now, this year, he had been eager to return home in time for the feast. Yet, I am told, he passed away later the same evening that he had planned to leave the hospital.

What I always liked best about the picture above is that it is actually two of my pictures, as I had taken the one of him in the baseball cap several years earlier.

Kenneth always spoke in a big, booming voice in which I never heard anything but warmth and friendliness. He was quick to laugh and always had a cup of coffee waiting, and a good meal, too.

And sometimes, he took me to dinner in restaurants, such as Pepe's North of the Border Mexican Restaurant in Barrow and Sophie's Station in Fairbanks.

This photo is one of several that hang as large portraits in the atrium of the Iñupiat Cultural Center in Barrow, all of which I originally shot for an issue of Uiñiq magazine that I dedicated to the Iñupiat Elders of that city.

Almost all those pictured in that atrium are now buried in the permafrost. I always love to go back to Barrow, but is also becoming a hard thing, because always, when I arrive, more and more of the familiar faces and voices that came to define America's farthest north city for me can no longer be seen or heard.

This is the Sophie's Station that I refer to. The day is May 10, 2003, and all those people gathered around Kenneth are scientists - Arctic Scientists, people who have studied the creatures and environment of the Arctic. These scientists have accomplished many things over the decades since World War II and have greatly increased scientific knowledge about the Arctic.

The reason that they came to Fairbanks this day was to pay honor to Kenneth, who was about to receive an honorary PhD from the University of Alaska, Fairbanks, for his contributions to Arctic Science. What they have accomplished would not have been possible without the work of Kenneth, and other Iñupiats.

Kenneth was there from the very beginning of the modern Arctic Science movement in Alaska. He employed his knowledge of the Arctic to enable the scientists to survive in an environment that will quickly kill the unsavvy. They relied on his powers of observation to enhance their own skills, for he could look at the ice and the sea and see things that neither they nor their instruments could detect.

When they built the Naval Arctic Science Laboratory, just north of the city of Barrow, they relied on Kenneth's knowledge of the permafrost, carpentry skills and Arctic constructions to help them design a building that would stand up to the harsh conditions that would batter it.

And stand up it did. Over 50 years later, NARL, now the main campus of Ilisagvik College, remains one of the most solid and useful buildings ever built in the Arctic.

I myself once kept an office and darkroom there.

At the time Kenneth received his PhD, I had no Uiñiq in the works and no place to run this series of pictures, so I gave him a disk. Beyond that, this is the first showing of most of these images.

As for the little stories from Kenneth's life that follow, they come from the Uiñiq that I published in the summer of 1996.

The scientists gathered around him above include John Kelley, Dave Norton, a gentleman whose name I do not know and Glenn Sheehan.

At a separate ceremony prior to commencement hosted by Alaska Native students at the MacLean House, John Schindler makes a joke about Toovak's mustache.

Kenneth Toovak - A Short Bio

Kenneth Toovak, Sr. - Utuayuk - was born in Barrow, April 19, 1923, to Timothy (Quilluq) and Ethel (Agnik) Toovak.

“The earliest that I can remember we didn’t have too much American food, for one thing. A bit of sugar, tea, coffee and flour, that’s all. We had the kerosene for the lantern and fuel. I remember we used to have lots of snowdrifts right in between the houses and the whole town is always kind of black, because of the smoke due to the heating of homes.”

Besides being a hunter, Toovak held many jobs. He worked for contractors exploring for oil on behalf of the Navy and in the construction of the Distant Early Warning station built by the Air Force to detect incoming Soviet missiles and aircraft, NARL and apartment complexes in Barrow. He was an original founder of the Barrow Volunteer Search and Rescue and the North Slope Borough Search and Rescue. He served the Mayor as Borough Safety Officer. He often volunteered his time to meet with students in the Barrow schools.

Toovak married Thelma Stine and they had 11 children, seven of whom are living.

“We were married September 16, 1940. My wife died on September 16, 1995. That’s where we’re at right now. It’s kind of hard, you know. It’s a good thing I have made a lot of friends who are good people. I felt great for them, deep in my heart – I appreciate what they did for me when I lost my wife. I didn’t know I made that many friends.

“I want to thank everyone of you that read the article. Thank you all from Kenneth Toovak.”

John Schindler, John Kelly and Max Brewer presented Toovak a print of a bowhead whale.

Kenneth Toovak Recites the Pledge

“When I finally decided to go to school, I was living in Browerville, (a Barrow subdivision) ” Kenneth recalled. “I walk to school in the morning, even through bad weather conditions. I have no excuse. I walk to school in the morning, walk home for lunch, walk back to school and then back home when class is over.

“I enjoyed being in school. The teachers were pretty generous. Our prinicipal always had a word of prayer before we go into the classrooms. That was great. I never forget that.

“Today, when I hear there’s some kind of problems in school, I always wonder on this lack of prayer in school. It always makes my feeling kind of low. I feel sorry for my government – why does it make a rule students shouldn’t have prayer?

“This is what I wonder about.”

Kenneth Toovak dances Iñupiat style with granddaughters Cassie (left) and Thelma (photos of both hang on the wall behind Kenneth in the opening image).

Kenneth Toovak Gets a Wife and Then Finds Rocks On The Ice

“I was a hunter when I was young,” stated Kenneth Toovak. “Whenever the weather was decent, I just had to go out and hunt. I was supporting my parents.” As world War II came to an end, Ned Nusunginya asked Toovak to take on a regular job, to work for a contractor hired by the Navy to explore for oil.

“I told him I don’t care about work, so I didn’t go to work when I was asked. This was 1945. Then, in 1946, I got myself a wife. Boy! It didn’t take too much time before I knew I should go to work. When I get a wife, I get that understanding real fast!”

Toovak helped in the exploration for oil and in the construction of the Dewline sites. In 1957, NARL head Max Brewer asked him to come to work full time, to assist in the scientific research of the Arctic.

In May of 1961, Toovak and Brewer flew far out over the ocean in a Cessna 180 in search of an ice floe on which to establish a research camp. “We go out about 110 miles. We see a lot of black spots on the ice below.” They called the pilot of a second 180, who radioed back that he saw the spots, too. “We land on one end of the ice floe, the other 180 lands on the other end.

“So we walked for awhile. We walked to that pile of rocks. Boy! It was a strange feeling, finding rocks on the ice!”

They scouted the entire floe, which was two miles wide and three miles long, and found a stretch of ice where a Douglas DC-3 on skis could land. Here, they made a research camp. Oceanographers, geologists, biologists and other scientists came to stay at the camp, which became known as Arliss Two.

Over the years, Arliss Two drifted about the Arctic Ocean. Eventually, it drifted so far from Barrow and so close to Greenland that it had to be supplied from Thule, Greenland. “People tell me that camp drifted around behind Greenland and melted. What a strange feeling it was to me, to find those rocks on that floe.”

Kenneth Toovak with Dave Norton and Glenn Shehaan.

Kenneth Toovak Survives an Airplane Crash

On a dark winter day, Max Brewer sent Kenneth Toovak out to an ice island to do some welding on a broken wench. Toovak traveled on a Lockheed C-130 Hercules. Strapped in the fuselage behind him, the pilot and co-pilot, was about 100 drums of fuel. The pilot missed his initial approach to the ice runway.

"I notice the plane didn't land, it goes back up in the air. Then I notice we approach the runway from the other direction. Then the C-130 touches the ice. As soon as it touches, he reverses his engines. We rise up high, bounce, then come down, hit hard. I notice there is a crack in the ceiling.

"We slide a bit, bounce up again, hit hard. Boy, that's the time we got real problems! The three of us are seated right in front of those drums. I notice the ceiling is really cracking; there is smoke in the ceiling. Then we hit a third time. I see through the window, the engine is on fire. The propeller is missing. I see the wing collapsed down. We slide for a bit and boy, we make a hard hit! We slide to the berm of the runway. We come to a stop.

"One of the crew opened the escape door. Boy! I was the first one to get off the aircraft, full blast! I have to run from the aircraft. I know the other two are right behind me. We hear it burning, we fear it might explode."

The crew snuffed the fire with extinguishers, then radioed NARL. "Boy, we were in kind of a sad situation that evening," Toovak says.

There were no aircraft available to come and pick up the stranded travelers. After several days, a de Havilland Twin Otter flew in from Resolute, in Canada's High Arctic. Toovak was flown to Resolute, then to Inuvik, NWT, and from there to Barrow.

"It was nine hours flying. I felt good when I got to Barrow. I felt that I was lucky to be alive."

John Schindler, Kenneth Toovak and Max Brewer (If you look closely, you can see both men in the photos hanging on the wall behind Kenneth in the opening image).

Kenneth Toovak Saves An Airplane

After the US Air Force abandoned a research station built on an ice island that had become stuck 87 miles north of Wainwright, Max Brewer decided to send Kenneth Toovak out to see if NARL could make use of it.

Toovak was flown to the island, where he found an abandoned DC-3 airplane. The sun had melted all the ice around the plane, except for a pillar about 15 feet high directly beneath the airplane where shade from the fuselage and wings had protected it.

It stood there, eery and silent, like a giant model on a pedestal.

Several abandoned buildings – shops, lodging, cook houses, etc., were also suspended on pedestals rising high above the surrounding ice.

NARL took over the base. Toovak was given the job of bringing the buildings down by Cat and setting them up on flat ice.

In a later year in May, a DC-3 landing on Arliss Two was blown off the runway into a pool of melt-water. Except for a bent propeller, it survived the mishap intact. Toovak was sent out to figure out a way to recover the plane.

“There was nothing to pull up the DC-3,” he recalled. “I thought maybe we could pull it up like a whale.”

Toovak secured two sets of block and tackle and anchored them in the ice - just the way hunters about to pull up a whale would do. He and another dozen workers tried to pull up the DC-3, but could not.

Not to be outwitted by an airplane, Toovak decided to attach the block and tackle to one landing gear at a time. The workers would then pull one gear up a bit, chop a hole at the wheel to prevent it from sliding back, then do the same to the other gear. They would zig-zag the airplane back and forth and up out of the water onto the landing strip.

Four hours after Toovak thought of this, the DC-3 was sitting on the landing strip.

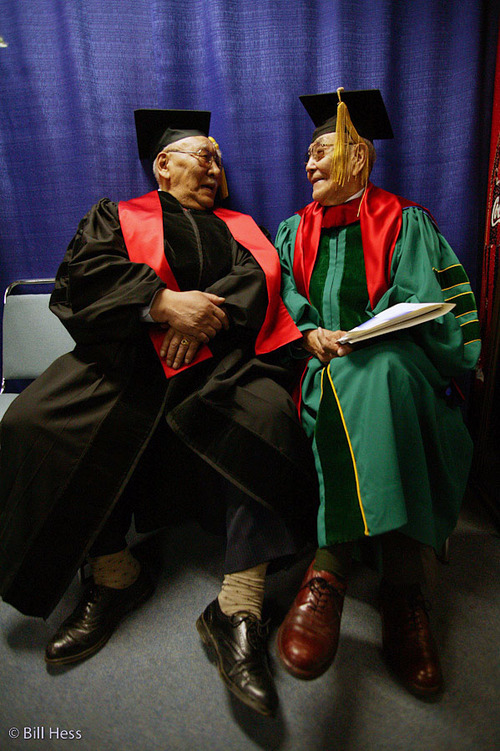

Before the ceremony begins, Toovak visits with Dr. Walter Soboleff, Tlingit, who will be delivering a commencement address. (Soboleff turned 101 earlier this month and was included in my recent AFN series. One day, I will devote a post exclusively to him - I hope during his life time.)

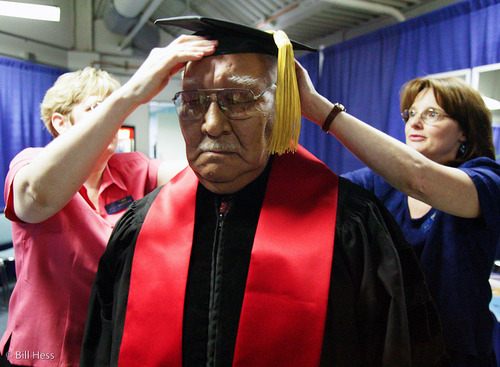

Kenneth is prepared for the graduation ceremonies.

Barrow's Suurimmaanichuat Dancers enter the hall for commencement. They drum not only for Kenneth, but for all those UAF students about to graduate.

Then UAF Chancellor Marshall L. Lind and another scholar drape Kenneth's shoulders with the sash that will identify him as as an honorary PhD.

Dr. Kenneth Toovak.

Dr. Kenneth Toovak, in the midst of his fellow PhD's. Ever since they became aware of the western concept of higher education, the Iñupiat have maintained that their knowledgeable elders and hunters are the intellectual equivalent of PhD's.

The scientists that I know who have worked closely with such Iñupiat do agree - and so does UAF.

Other traditional Iñupiat scholars who have received honorary PhD's from UAF include the late Dr. Sadie Neakok, the late Dr. Harry Brower, Sr. and the late Dr. Harold Kaveolook.

After being congratulated by granddaughter Thelma, Kenneth touches the head of his great-grandchild.

Kenneth Toovak receives a congratulatory hug.

One day last May, as I walked down a Barrow road, a vehicle pulled up alongside me and stopped. It was Kenneth Toovak. Whenever I go to Barrow, sooner or later, this always happens. Or so it has in the past.

His funeral service will be held Saturday. I have not yet seen an announcement with the time and place, but where else could it be, but at the Utqiagvik Presbyterian Church? And if you are in Barrow on that day, you will know what time.

My condolences to all the family and friends. God bless you all and thank you for sharing this wonderful man with the world, and with me.