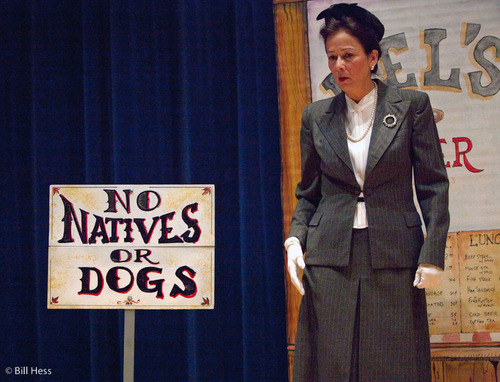

There was a reason that I drove to Anchorage yesterday and got myself caught in falling ash - to see Diane Benson act in her final performance of the one woman play, "When My Spirit Raised It's Hands." Here, at the end of the play, she takes her final bow as Tlingit civil rights heroine Elizabeth Peratrovich.

Diane first put the play together over a decade ago to create a simple but effective device to teach Alaska schoolchildren something about how Alaska's Natives had to fight racism and prejudice to secure their rightful place in their own homeland.

Afterward, she explained that she feels it is time for a younger Native actress to step up and take the play over. "I don't want to be the grandmother forever playing a woman in her thirties," Diane explained.

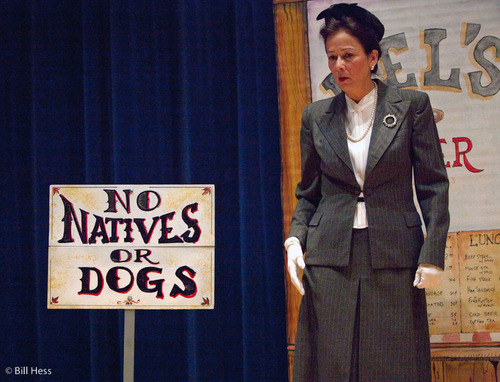

In 1941, Elizabeth Peratrovich moved from the tiny Tlingit village of Klawock to Juneau with her husband Roy. There, she was surprised and deeply hurt to find signs, such as this one depicted outside "Mel's Diner," that banned Natives from certain establishments. These are the actual words that Elizabeth found herself confronted with - and such signs were common in Alaska cities, from Juneau to Fairbanks to Nome.

Elizabeth was the Grand President of the Alaska Native Sisterhood and Roy the Grand President of the Alaska Native Brotherhood. They teamed up to lead the fight for civil rights for Alaska Natives in Juneau, the territorial capital.

Elizabeth was the Grand President of the Alaska Native Sisterhood and Roy the Grand President of the Alaska Native Brotherhood. They teamed up to lead the fight for civil rights for Alaska Natives in Juneau, the territorial capital.

The US entered World War II and a higher per-capita percentage of Alaska Natives and American Indians entered the military to fight the Axis then did any other racial group.

To make a statement, Elizabeth the "No Native or Dogs" moved the sign from in front of the diner to the recruitment office.

Elizabeth and Roy allied themselves with Governor Ernest Gruening, who expressed revulsion when they showed him what kind of discrimination Alaska Natives had to face. Along with allies in the Territorial Legislature, they helped draft an anti-discrimination bill. The effort took years, but finally Alaska's Anti-Discrimination Act came before the legislature in February, 1945.

The Act passed in the House, but ran into stiff opposition in the Senate.

"Who are these people, barely out of savagery, who want to associate with us whites, with 5,000 years of recorded civilization?" mocked Juneau Senator Allen Shattuck.

Another Senator proclaimed that he should not be forced to sit in a theatre alongside an Eskimo, because the Eskimo smelled.

It was after that, in the moment depicted above, that the spirit of Elizabeth Peratrovich raised its hand. Her right to speak was honored. She stepped before the Senate.

Standing between the American and Alaska flags and the traditional clan blanket that Identified Elizabeth as a Lukaax.adi clan of the Raven moiety, Diane recites the speech that the ANS Grand Camp president delivered that day.

"I would not have expected that I, who am barely out of savagery, would have to remind gentleman with 5,000 years of recorded civilization behind them of our Bill of Rights. When my husband and I came to Juneau and sought a home in a nice neighborhood where our children could play happily with our neighbors' children, we found such a house and arranged to lease it. When the owners learned that we were Indians, they said 'no.' Would we be compelled to live in the slums?...

"There are three kinds of persons who practice discrimination. First, the politician who wants to maintain an inferior minority group so that he can always promise them something. Second, the Mr. and Mrs. Jones who aren't quite sure of their social position and who are nice to you on one occasion, and can't see you on others depending on who they are with. Third, the great superman who believes in the superiority of the white race..."

Shattuck challenged her. He asked if the act of passing the bill would actually end discrimination.

"Do your laws against larceny and even murder prevent those crimes? No law will eliminate crimes but at least you as legislators can assert to the world that you recognize the evil of the present situation and speak your intent to help us overcome discrimination."

Peratrovich finished to silence - and then loud applause. The Act passed, 11- 5: 19 years before the US Civil Rights Act was enacted in 1964.

After the play, Diane sat down to take questions, but was interrupted by Tony Vita, who presented her with a plaque from Roy Peratrovich, Jr. Her emotion showed.

If you would like to read what Roy Jr. wrote, just click this picture.

If you would like to read what Roy Jr. wrote, just click this picture.

Unfortunately, Elizabeth Peratrovich died before Alaska became a state in 1959. Diane came along too late to meet her, but as a youth she did get to know Roy. Diane had led a tough life, had been in many foster homes and had experienced abuse, both physical and sexual.

Roy firmly told her not to drop out, but to finish school and make something of her life. She agreed that she would.

Just as Elizabeth predicted, there were those who still discriminated against Natives, despite the act. As a girl, Diane once went into a restaurant in Ketchikan where a waiter refused to serve her.

Her father complained. The waiter was fired. That might not have happened, had no such act been in place. After the play, Diane stressed that racism is still strong in Alaska, and urged all present to continue to fight against it.

Diane is the mother of Latseen Benson, an Army veteran who lost his legs fighting in Iraq. As a past candidate for Congress and before that, for Governor, Benson has strongly stood for the rights of veterans.

In this, she also echoes Elizabeth Peratrovich, who, as ANS President, organized fundraisers and drives to help World War II soldiers of all races, including prisoners of war.

When her son went to war, Diane was helped through the turmoil of all that happened by her cat, Romeo. The story is right here, on the No Cats Allowed Kracker Cat Blog.

Sunday, April 19, 2009 at 1:11AM

Sunday, April 19, 2009 at 1:11AM