Five veterans: Gilbert sees bodies pile up in Korea, Iñupiat mother Irene stands with pistol on hip and baby on back to face Japanese, Strong Man returns from Iraq to walk again; two more

Thursday, November 11, 2010 at 12:57PM

Thursday, November 11, 2010 at 12:57PM

Once in awhile, I still dream about the war* Gilbert Lincoln of Anaktuvuk Pass says of his experience in Korea. “I always be tired when I wake up. I don’t tell my wife about it. I don’t tell my children. I don’t want to worry them.”

Lincoln turned 21 in 1952, was drafted into the Army and sent to Fort Richardson, where a rifle was placed in his hands. Born in Noatak, he had grown up with guns. As a boy, he had followed his grandmother out reindeer herding. He attended school in Noatak, and spent much time, rifle in hand, roaming about the countryside, hunting.

This rifle had a different purpose.

After basic training, Lincoln was sent to San Diego. “They were calling for volunteers, so I volunteered. I guess I volunteered for the wrong job. The next thing I heard, they were shipping a bunch of us guys out. There was a lot of people on that boat. We landed on Parallel 46, not too far from Peking and right by Seoul someplace.

“We go into the front, every third week. It is pretty rough. No place to stay. Some people call it a one way ticket.”

In Korea, Gilbert Lincoln discovered the horror of leaving on patrol with eight or nine men and returning with only half. One time, he set out on patrol with 10 men, only to come home alone. Lincoln, who was the lone Iñupiat in his company, became a good buddy with a soldier from California and another from Texas, then lost both in combat.

“After I lost those two, I didn't have no more interest,” Lincoln remembers. “The only strength I got is from my Lieutenant. He said, ‘If you don't shoot, I will kill you.’ I think he was trying to give me courage. It worked real good.”

In Anaktuvuk Pass, Gilbert Lincoln is known as a storyteller, but he keeps his stories of the war pretty much to himself. “The only thing that keeps you up is the Good Lord, watching down. Like they say, he is right there by you, all the time. I had a pocket sized Bible the chaplain give me. I always read it.”

After the war, Lincoln returned home to Noatak. “I was glad to come home, but it was pretty rough, not too good.” Friends and family did not understand what he had been through and he had no way to tell them. “I would get flashbacks. Sometimes, when you get it, you get real jumpy, kind of nervous. It is hard to get rid of. I was afraid if I stayed in Noatak, I would kill somebody.”

Lincoln moved to Kotzebue, where he worked as a power plant operator for the White Alice Project, a radar program designed to detect incoming Soviet missiles. There he met Ada Rulland from Anaktuvuk Pass. They were married in 1962. Gilbert joined the Alaska National Guard and served as an Eskimo Scout for 12 years.

Ada brought him home to Anaktuvuk in 1972 and he has been there ever since. He and Ada raised six children including two adopted. “It’s a good place,” Lincoln says of Anaktuvuk. “Real good country.”

In Anaktuvuk Pass, Lincoln is known to have the gift of the storyteller. When he goes hunting, friends and family eagerly await his return, for they know he will have some good stories to tell. He shares these stories over the CB radio. Even before he begins to speak, other villagers sit by their radios and grin, for they know that whatever accounting Lincoln gives them of his adventures with caribou, wolves, wolverines or whatever he encountered will be well worth hearing.

But he tells no stories of his combat in Korea. These he keeps to himself.

“I’m proud of my military service. I’m proud of my country, in fact. My pride comes from serving my country as a US citizen,” Lincoln says, adding that he gets very hurt and angry when he sees news reports of any Americans burning or desecrating the US flag.

“A lot of people die for that flag. I’ve seen a lot of them piled up.”

Something else bothers Lincoln.

“You never hear about Korea,” he explains. “People hardly know about Korea. I would like to see the Korean vets get a little attention.”

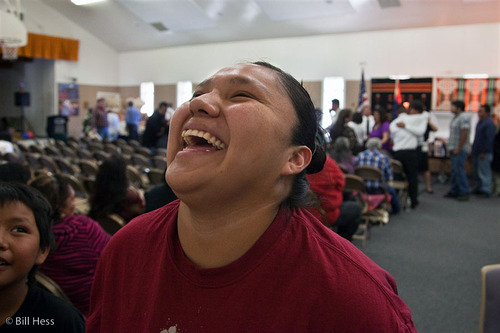

In the spring of 1942, the people of Barrow heard that the Japanese were coming to bomb the village.

"We hear seven Japanese planes are coming to bomb Barrow, but they freeze and have to turn back," Irene Itta* remembers. A total blackout was imposed upon the community. All windows had to be sealed off so that no light escaped outside. The famous Major "Muktuk" Marston came to town to help organize the Territorial Guard. A tower the height of a house was built from empty steel drums just outside of town. There, Guard members stood sentry, scanning the skies for Japanese planes.

Whaling season arrived. The men had no time to stand on a tower of barrels to watch for incoming Japanese airplanes.

They turned to the Barrow Mothers’ Club for help. Irene’s own husband, Miles, was stationed in Nome with the U.S. Army. Still, she did not hesitate when she was asked to volunteer for guard duty.

Irene had a tiny baby girl, Martina, who depended on her. Still, someone had to go watch for the Japanese, and that someone was Irene Itta. Early in the morning, she reported for duty. She wore her parka, and in it, tucked snugly onto her back, was baby Martina. A guardsman issued her a pistol, fully loaded and with extra bullets, and strapped it to her waist.

"He didn’t even show me how to use it," Itta muses.

At 8:00 AM, Itta took her post atop the barrels. She had been instructed to bang upon the barrels at the first sight of anything in the sky.

So she stood there, a baby on her back and a pistol on her hip, atop a tower of steel drums, for 12 hours straight, in the cold, scanning the sky for incoming Japanese airplanes. Fortunately, baby Martina slept a lot. When she would awake, Irene would breast-feed her, there on the tower.

At 8:00 PM, Itta was off duty. She had spotted no Japanese.

"Today, they wouldn’t do that," she states. "They’d probably want to get paid. I did it so the people can have a safe place to go. No one knows about it. It was never in the papers, not on the radio. I always tell my son, when I die, I want a special ceremony. I want a flag, I want a salute, with the guns, because I served my country in the territorial guard."

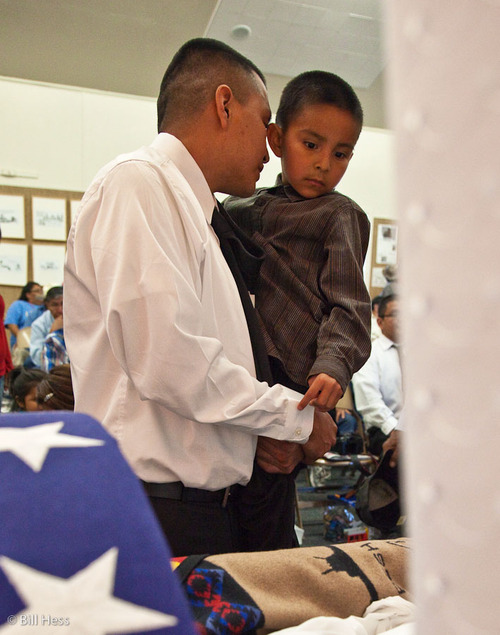

My post of November 3 included a picture of Latseen Benson who had come to the post election party for Ethan Berkowitz and Diane Benson, Latseen's mother, following their unsuccessful run for Governor and Lt. Governor. Latseen was standing in that picture and I mentioned that it was good to see him standing.

This is why.

This is Latseen, at Ted Stevens International Airport just before the Fourth of July, 2006. He has just rolled back home into Alaska for the very first time after losing his legs to an IED in Iraq. His wife Jessica stands behind him, his mother, Diane, in blue to his side.

He is greeted by a welcoming group of his people, the Tlingit and Haida.

Williard Jackson of Ketchikan drums and sings for him.

Latseen means "Strong Man" in Tlingit. A few days later, Latseen races his way to one of several gold medals that he won in the 2006 National Veterans Wheelchair Games - held that year in Anchorage.

This morning, Veterans Day, I went to breakfast at Mat-Su Valley Family Restaurant, because almost always I see a number of veterans there, identified by the words and symbols on their caps and jackets that tell their branch of service and what war they fought in.

So I thought I would spot such a veteran, or maybe a couple, and photograph them for this blog.

But when I arrived, I could see no obvious veterans at all.

"There were several here, earlier," my waitress told me.

This young man and little girl sat at the table next to mine.

As I ate, I kept waiting for an obvious veteran to appear, but none did.

Then my food was eaten. I wondered - could this gentleman be a veteran?

He looked like he could - but then veterans come from all of us, so anyone old enough to have served could look like a veteran.

"Excuse me, sir," I asked. "Are you by any chance a veteran?"

"Yes," he said. "But I served stateside."

Perhaps. But at any moment, had the need arisen, he could have been sent into harm's way.

This is him, Ray, U.S. Army, who served in the early and mid-90's, all of it stateside. He is with his niece, Amber, better known as Pickles. They were about to head out to see a movie together and were excited to get going, so I asked no further questions.

I was embarrassed to discover that I had forgotten to put a card in my camera. I had to resort to my iPhone.

And on the Parks, Pioneer Peak in the background, this Marine passed me. I know nothing about him - when he served, where he served. All I know is that he goes by "Semper fi," as noted in his rear window.

*The stories of Gilbert and Irene are a from a series on Native Veterans, with initial funding from the Alaska Federation of Natives, that I did over a decade ago. Gilbert, Irene and Miles have all since passed on. Irene got her flag and her burial with military honors.

Sadly for me, I did not learn about her death until after her burial, or I would surely have been there to photograph this honor that she had earned.

I had planned to run a dozen or so such stories in this post, but I just don't have the time for now.

While I took the series as far as the available funding would allow, I never finished it. There were a number of folks who expressed an eagerness to help me find funding, but none succeeded. Still, as the opportunity presents itself, I continue to work on this.

I will photograph veterans, Native and otherwise, anywhere and anytime that they become available to me. To the degree that they wish, I will tell their stories as well.

I am sad, though, that I was unable to get the funding that would have allowed me to continue seeking veterans out in small villages across the state, because so many, especially from World War II and Korea are gone now. And those from Vietnam are going at an increasing rate.

As the opportunity presents itself, I will continue to work on this project - for as I long as I am able, funding or no funding.