I am proud to join in the praise for my friend of nearly 30 years, Barrow novelist Debby Dahl Edwardson, who has just been named as a finalist for the National Book Award for Young People's Literature.

"Wait a minute!" the indignant reader suddenly shouts in protest. "If Debby is the finalist, then she should be the center of attention! Why is she looking at her husband? Why is he the one doing the talking, not her? This is all wrong!"

No, it is not wrong. It is right. Debby is the first to tell you - she is the writer in the family, but husband George Edwardson is a master story-teller and a continual source of inspiration and raw material for the words that she writes.

When their children were small, Debby would read stories to them. George would tell them stories - wonderful stories, Debby says, stories that never repeated themselves but always went somewhere new - stories based on the life that George knew as an Iñupiaq hunter and scholar in the traditional sense.

She always knew that if told they could hear one but not the other, her children would choose the stories George told from his mind and soul over the ones she read.

Over the years, she heard him tell many stories about his days as a student at the Copper Valley School, the now-closed Native boarding school in Glennallen run by the Catholic Church.

Some of the stories were funny. Some of the stories were inspirational. Some sad - many were downright hard and even tragic. Most were a combination of all these things and more.

Then, about a decade ago, Debby accompanied George to a reunion of the Copper Valley alumni. There, she was deeply moved by the familial connections and shared experiences that bound the students together.

She saw it as a story that needed to be told. George agreed. Debby then crafted a screen play and submitted it to the Sundance Institute. She received a hand-written rejection informing her that it had ranked high, but not quite high enough. In 2003, she began reworking it into her Master's Thesis.

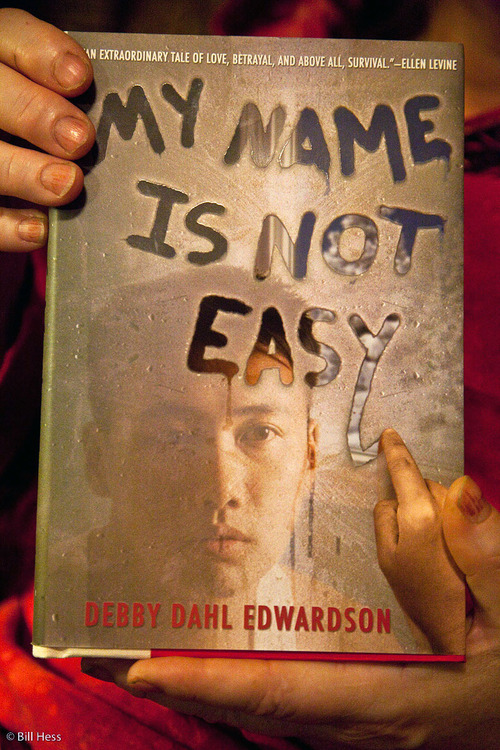

And now it is her third book, My Name is Not Easy, behind Whale Snow and Blessings Bead, and a finalist for the National Book Award. Debby stresses that it is not a book about Copper Valley School per se - it is a work of fiction, inspired by the stories of her husband but relevant to the boarding school experience experienced by so many Alaska Native students.

She also stresses that it is not a book about victimization. Like the real-life graduates of boarding schools, her students did experience many hardships and wrongs, but they also formed bonds, learned about the western world and many went on to work together to advance Native rights.

The book was published by Marshall Cavendish and edited by Melanie Kroupa, who long ago saw talent in Debby and, like an editor of old times, stuck with her and nourished her through five years of rewriting and reworking until the book was just right.

When she was about three, Debby would often stand in her father's den and gaze at the many books that filled his shelves. She could not yet read or write, but she understood that there was power and stories between the covers of these inanimate objects. She knew she wanted to be part of those books - as both reader and creator.

When she was in the third grade, her teacher gave her an assignment to make a diary about a family camping trip. She wrote about what it felt like to sit in the front of the boat as it made its own waves while pushing its way through the lake.

After she handed in her paper, she noticed her teacher show her story to another teacher. She could see that her teacher was boasting about her. She knew then that she had the ability to make the power of words her own and with that power could move other people.

Conversely, in high school, she asked her English teacher if she believed she could be a writer. "No," the teacher responded.

"That's the one you want to invite to the awards," George interjects sardonically.

In college, an instructor convinced her that she could write articles for publications.

By the mid-70's, she found herself living in Barrow, where she attended a public hearing on a an environmental impact statement dealing with offshore oil development.

There, a young man stood up and took apart the environmental impact statement piece-by-piece. "When he was done, he had totally destroyed that environmental impact statement," Debby remembers. She wrote the event up and it became her first article published in the mainstream press: We Alaskans, the then Sunday magazine of the Anchorage Daily News.

That young man was George Edwardson, who continues that fight to this day. The two had no idea that they would one day wed and make a family together.

Next, she went to work for KBRW, the Barrow public radio station, reporting, writing, and reading news articles.

One day, Jean Craighead George, the famed Children's author and mother of Craig George, renowned bowhead biologist, came to Barrow and agreed to an interview. Afterward, Debby told George that she had always wanted to write stories for young people.

"She looked at me and said, 'well, do it."

Struck by the simplicity of the answer, Debby did, indeed, do it.

As for George, he says that "of course" he is proud of his wife. "I have always been." He adds that he was not surprised when she was named a finalist, because he has known for decades that such honors would come to his wife. Even Debby's mother, who did the painting on the wall behind him, had always known, George, who puts great stock in the knowledge of mothers, added.

Debby is retired from Ilisagvik College, but still serves as an adjunct professor. She was also just reelected to the board of the North Slope Borough School District. As part of her campaign, she ran an ad on the Eskimo channel that stated that education is the passing of the soul of a culture from one generation to the next.

"That's what your writing is, too," George told her.

The announcemnt of the winner of the National Book Award will be made at a fancy dinner next month in New York City. Naturally, George has been invited to attend alongside his wife. He has consented to go to New York, but not to the dinner. "It's black tie," he explains. "They're not going to put a tie on me!"

Last night, when I visited them, George was busy making ulu knives - some very large, some very small. He will convert a pair of tiny ulus into a set of ear rings for his wife to wear to the dinner where the announcement will be made.

Believe me, I stand by George on the whole black tie thing. I understand perfectly. Even so, I hope that when Debby enters the fancy place that George walks in alongside her, dressed in his classiest Iñupiaq clothing. If so, no man there will be more elegantly dressed than will be George Edwardson of Barrow, Alaska.

Well, there's lots more I could write about my friends, Debby and George Edwardson, but I've got to get up early to catch a plane to Atqasuk. And anyway, in no time at all, there's going to be lots of writers, even from outfits like the New York Times, writing about Debby and George and they will surely cover all the gound that I have skipped over or just didn't think to write about.

View images as slides

Saturday, October 15, 2011 at 10:50PM

Saturday, October 15, 2011 at 10:50PM